My thinking about this story has developed, and my research has continued, since I wrote these pages. I have corrected and expanded upon them in Tar for Mortar: "The Library of Babel" and the Dream of Totality, available open access from punctum books.

The first paragraph of Borges’ “The Library of Babel” offers a minute description of the universe he has doomed his librarians to inhabit. Which is why I was shocked to reread the story recently and discover my mental image was completely wrong. He describes a vast architecture of interconnecting hexagons each with four walls of bookshelves and passageways leading to other identical hexagons. I had made the assumption that six walls minus four walls of book shelves equals two such passageways. I read to my astonishment:

The arrangement of the galleries is always the same: Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon's six sides; the height of the bookshelves, floor to ceiling, is hardly greater than the height of a normal librarian. One of the hexagon's free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first-identical in fact to all.

One of the hexagon’s free sides opens onto a vestibule - how could this be? So much of the story told by our narrator conjures endless, desolate expanses of hexagons, repeating infinitely and inspiring both the reverence of the God who created them and despair at a life trapped inside them. But this would only be possible if the hexagons had two openings each - otherwise the structure would terminate at its first junction.

I found an answer in Antonio Toca Fernandez’ “La Biblioteca de Babel: Una Modesta Propuesta”, to which I am greatly indebted. The first version of Borges’ “La Biblioteca de Babel”, published in 1941, contained the same description, excepting two words: each hexagon contained 25 bookshelves, five each covering five walls. In 1956 Borges changed the text, presumably because he had recognized his error.

This is the trickiest part: he changed twenty-five to twenty, changed “each of the walls less one” to “each of the walls less two,” but left only a single opening to an adjacent hexagon. Such an edit is incomprehensible unless Borges intended to open the fifth wall as another passage allowing for the interminable continuity of his labyrinth. It's almost as difficult to imagine the author recognizing two of his errors in this short phrase while creating a third. That must be the case, unless he had decided to create a labyrinth in which only his most careful readers would become lost, consisting of an impossible yoking of inconsistent architectures and irreconcilable texts.

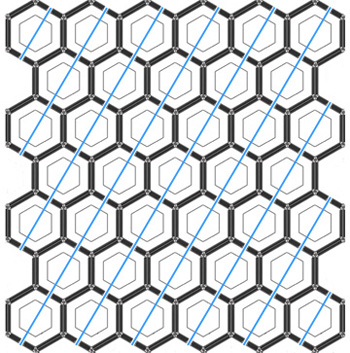

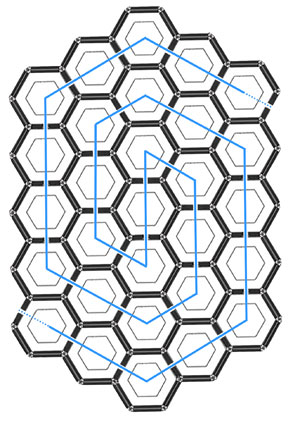

If we accept the reading that each hexagon has two connections to adjacent chambers, this still leaves a great diversity of possible organizations. The easiest assumption to make is that each hexagon has its passages on two opposing walls, creating a continuous pathway. This structure presents a problem, however (see adjacent).

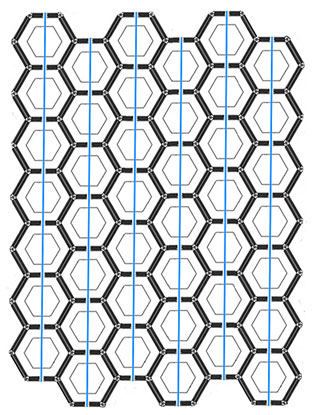

These paths would persist as such to infinity, without the librarians of one corridor ever being able to cross the minuscule distance separating them from the adjacent throughways. They might be separated by no more than a bookshelf throughout their lifetime from others they could never reach. Borges does say, however, that the hexagons are tiered, with each level connected by vertiginous spiral staircases. If the passages above or below had a slightly transposed arrangement (see adjacent), then the parallel corridors could be accessed by going up one flight of stairs, passing to an adjacent hexagon, and descending again.

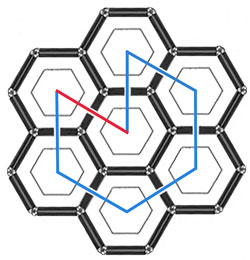

Would it be possible for all the hexagons on a single floor to be connected? This would require a more complex design. Imagine a path radiating from a “central” chamber (in the library, as in the infinite sphere, the “exact center is any hexagon” and the “circumference is unattainable”). Such a path quickly encounters a problem (see adjacent).

The path must either return on itself, creating a closed circuit inaccessible to the outside (there is one somewhat cryptic reference to “a hexagon in circuit 15-94” in the story - the circuits that the librarians have numbered may be just such self-contained patterns), or radiate outwards, leaving the central hexagon with only one opening.

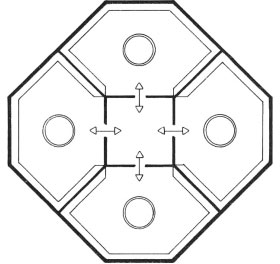

If we believe, as does our narrator-librarian, in the infinity of the library, there must be at all times two open paths, two “liberties,” as Go players would call them (see adjacent). Two paths emerge from the “central” chamber (there are only ever relative centers in such a structure), and reunite at infinity, which is another way of saying they never meet. If one of these paths simply came to an end, reaching a hexagon with no hexagons beyond it, that hexagon would have only one entrance, breaking the symmetry established by Borges.

A strange realization lurks in this design: if we extend its spiral by a few more involutions, it would become, within the limits of our frame of reference, indistinguishable from the design with which we started. Those paths which seemed to stretch out to infinity, lonely and isolated, could actually have been switchbacks, connected at great distances. This structure is reminiscent of Richard Feynman’s metaphoric description of antimatter: “It is as though a bombardier flying low over a road suddenly sees three roads and it is only when two of them come together and disappear again that he realizes that he has simply passed over a long switchback in a single road.” There’s no difference, at the extreme reaches of an infinite structure like the one we are imagining, between the seemingly fragmented structure with which we began and the seemingly unified one we have reached. A finite creature could at most only believe that the interminable corridors met at infinity, without ever reaching that point.

All of this invokes one of Borges’ favorite themes, the line and the circle as they relate to the infinity or finitude of existence. At the end of Borges’ “The Death and the Compass” (“La Muerte y La Brújula”), the trapped protagonist longs only for a simpler labyrinth: "There are three lines too many in your labyrinth…I know of a Greek labyrinth that is but one straight line.” And his captor replies: “The next time I kill you…I promise you the labyrinth that consists of a single straight line that is indivisible and endless.”

We too could imagine a simpler labyrinth, a single string of hexagons too long for any mortal to traverse, without the capacious pits that grant a view on infinity and the knowledge of other paths. Anyone with the misfortune to find themselves inside such a space would never know if she walked an infinite line or a circle, if the ends of her path met or not. An infinite circle, Borges points out in another tale (“Ibn-Hakam al Bokhari, Murdered in His Labyrinth”), would be, for finite eyes, indistinguishable from a line (were its circumference visible at all). “…They had arrived at the labyrinth. Seen at close range, it looked like a straight, virtually interminable wall…Dunraven said it made a circle; but one so broad its curvature was imperceptible.”

These lines immediately follow the complaint of his companion:

‘Mysteries ought to be simple. Remember Poe’s Purloined letter, remember Zangwill’s locked room.’

‘Or complex,’ replied Dunraven. ‘Remember the universe.’

Tar for Mortar | Massa por Argamassa | Seen from Within | Tower of Babel | Uninventional